Transition in Education

Nepal’s political transition might have ended with the establishment of three tiers of government but the transition has just started in other sectors, including education. The constitution of the country has bestowed a lot of authority to local governments followed by provincial governments, with the federal government mostly having a coordinative and facilitating role. However, the centre which has enjoyed total authority for decades will not give up the reins to power so easily. It seems unlikely that the federal government will be content with their new facilitative role as it is already moving in regressive ways. The continuation of District Education Offices as Education Coordination Units, despite the fact that the Local Level Governance Act categorically demands that they be closed by mid-April reflects the center’s mindset.

The officials at the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology argue that the presence of federal government units is required until the local and provincial governments are fully settled. They say such units are necessary to act as a liaison between the federal, provincial and local governments. Logical as it may sound, the actions of the central government would suggest that such units are for more than just plain facilitating. In several parliamentary meetings, lawmakers, including those from the ruling parties, have criticised the centre for trying to undermine the authority of the local and provincial governments.

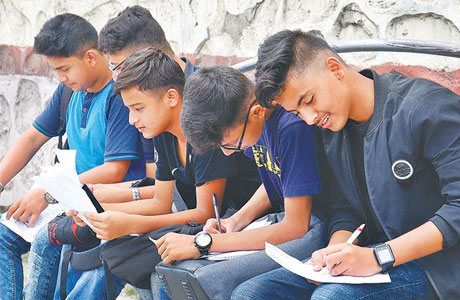

They demand that the federal government help empower the newly-formed governments rather than imposing its authority over them. The ministers say there will be a gradual delegation of authority with the seven provincial and 753 local governments still taking their shape. The Constitution of Nepal has delegated the authority over school-level education to the local government while the provincial government manages state universities.

In reality, the local government’s authority in education has merely been limited to conducting the grade eight examinations and providing salary to teachers. While it’s a fact that the local governments aren’t prepared to handle all the authority bestowed upon them, is it equally true that the federal government is unwilling to invest in expanding the capacity of local governments. The experts say that rather than encroaching upon the jurisdiction of local and provincial governments, the centre should focus on preparing Acts as per the statute and restructure the government entities accordingly.

The constitution makes it mandatory to come up with all the Acts related to fundamental rights, which include education, by September 19, while the remaining Acts need to be in place by March 4 next year. The major challenge for the government is managing free education up to grade 12 and compulsory education till grade 8. As the private sector now has around 20 percent share of the education market, implementing free and compulsory education in private academic institutions will be a challenging task for the government. Private educators who have enjoyed total liberty by influencing the bureaucracy and political leadership so far will not want to compromise. Many of the private school operators have a good rapport with the current leadership, which means there is hardly any chance for state authorities to implement policies that contradict private interest.

The private sector has openly warned the government to not promulgate provisions that would curtail their interests. For instance, they slammed the recommendations of an expert panel led by education experts which had suggested that only a gradual phasing out of private schooling can ensure free education up to the secondary (grade 12) level as envisioned in Article 31 (2) of the Constitution of Nepal. The panel had suggested that the government should facilitate shifting private educators towards university and technical education, gradually leaving the task of providing school education to the government.

Private educators have rejected these claims and accused the panel members of simply not understanding the situation. Under pressure, the government is for now allowing the private institutions to run in the same way they did in the past. The drafting process of an Act to ensure the fundamental rights of the citizen has begun which broadly says that education will be free only in schools that are managed by the state. That means that any student, in order to enjoy the fundamental right to free education, will have to study in the public schools. This not just contradicts the spirit of the statue but also the five-year strategy of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

It is fact that the private sector has as huge stake in the education but the implementation of the constitution is the government’s key duty and it is high time to find an amicable solution. The upcoming Acts should have clear provision in managing private schools as envisioned in the constitution. It becomes the duty of the federal government to have adequate consultations with all stakeholders to ensure that every child gets free education up to grade 12 no matter where they study.

The increment in the government investment is the pre-requisite to make it happen. Despite its global commitment, the Nepali government has never allocated 20 percent of its national budget to education. Instead of increasing the share of education in the national budget, the opposite has happened. If the current government is committed to its goals, it has to bring the entirety of school education under its ambit while also putting due focus on uplifting the quality of the public schools. Similarly, the private sector which has a large investment in education should be given every support the government can to help them gradually shift towards higher and technical education as recommended by the expert panel.

source: Binod Ghimire, The kathmandu post, 1 July 2018

Posted on: 2018-07-01